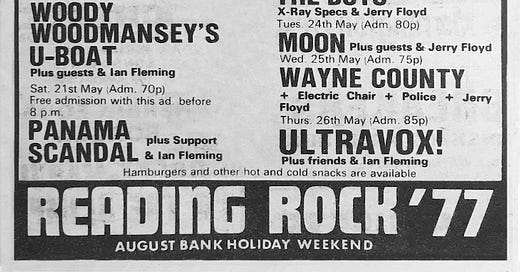

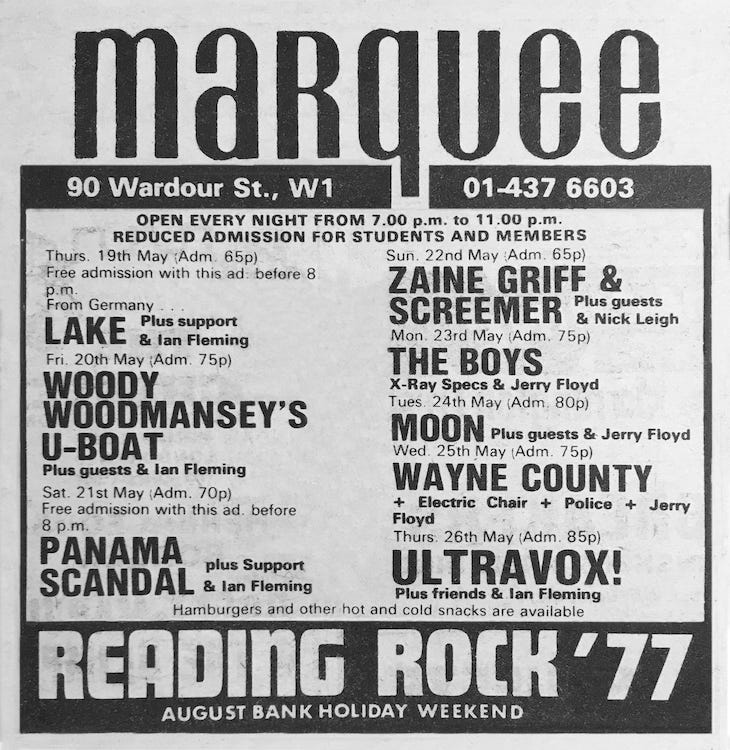

On 25 May 1977 The Police made one of their very first live appearances at the iconic and legendary Marquee Club on Wardour Street, London, as support to Wayne (later Jayne) County and the Electric Chairs. It was 75p to get in, equivalent to about £6 in today’s money, and for their appearance Sting, Stewart and Andy would have received the princely sum of about £20 - about £160 today.

Sometime in the mid 80s, after a bout of super inflation and soaring fuel costs, the fee for being the support act given the lucky opportunity to perform on a headliners show settled at £50. When I promoted my very first show in 1984, second wave punk heroes 999 headlining, I genuinely don’t recall who the support act was but they were contracted for £50. 10 years later, when I promoted Space, the support act Catatonia received £50. A full 13 years later, 2007, Adele earned herself the princely sum of £50 supporting Jack Penate on tour. Tonight, somewhere in the UK, a support act on a grassroots music venue tour will take their contract out, show it to the promoter, and claim their £50. Going all the way back to 1977, and that Wednesday night in Soho, across the last 46 years we have cut the value of the support band fee by the equivalent of £110. In actual cash terms, Gordon Sumner and his chums have just been offered £6.29.

Now plainly support acts aren’t doing it purely for the money. That dreaded word ‘exposure’ also gets a look in, as does the fact that going out as the support act is a skills and experience exercise that most musicians recognise is an important part of their growth and development. Acts I’ve seen as support in small venues include Coldplay, Ed Sheeran, Snow Patrol, and Stereophonics, all acts I would imagine would have realistic expectations about what they were going to get in terms of a fee for doing it and a lot to say about the value of doing it anyway. Even the Musicians Union Fair Play Venue guide recognises that performing as the support act will have a significant impact on what you might receive purely as a financial reward.

These weekly musings on ‘things we really need to think about in the music industry’ include, as regular readers already know, one point in each column where I say ‘but’, so here’s this week’s:

A 4 hour rehearsal space booked with Pirate Studios for a 4 piece band is £26.50. One set of bass strings is £17. One pair of drumsticks £7. A transit van with an 80-litre tank costs £138.75 to refuel. One room at the M5 Junction 26 Premier Inn near Worcester is £123 per night. Breakfast for 4 at Wetherspoons is £27.52. One person to act as a driver, tour manager, sound engineer and road crew, even if you paid them minimum wage and pretended they worked for only the statutory 8 hours, would be £81.44. Note: If you know anyone prepared to do all that work for £81.44 a day, please, please don’t hire them.

Water for the van, strings, sticks, something breaks and it needs repairing. The singer gets hungry and wants a Mars Bar: That’s 2% of your money for that day gone. Let’s be realistic, if you can get from one venue to the other with a band that is fully equipped, has eaten some food, and slept well enough to play, you won’t have any change from £500 per day.

It’s important to understand that this cost per day exploded in comparison simply to the fee that The Police were paid in 1977. £500 a day in 2023 appears to equate, in cash value terms, to £62 in 1977. But the reality is that inflation in every single aspect of the costs required to keep an act on the road significantly exceeded inflation across those 46 years. The £20 handed to The Police left them with nothing to spare, and maybe making a small loss. The £50 handed to a support act tonight leaves them in a financial hole of at least £450.

In times gone by, record labels used to step into the hole with something called ‘Tour Support’. This was an advance that would be offset against future royalties predicted to be earned from record sales generated by the growth in the acts reputation, and therefore income, by the touring. Sometime around 2004/2005, as the digital revolution besieged their income streams, the labels reacted by pulling out of this activity. In response, headliner fees went up significantly - without tour support, most headline acts couldn’t afford to tour and promoters and venues simply had to reset the distribution of income to increase the fees. Headliner fees have continued to grow exponentially, with headline artist fees at small venues taking an ever increasing percentage of the total income for an evening. But Support Act fees remain stuck on £50. They’ve been stuck there for at least 40 years and no one really knows how to un-stick them. While we can accept and acknowledge that the support act won’t ever be financially sustainable as an activity in itself, the reality is that we have made economically unachievable.

There are a large number of obstacles to resolve this challenge. We have the rather simple point that almost no one is making money at this level of touring. In 2022, grassroots music venues collectively lost £79 million putting on live music, a loss they (just about) covered by selling alcohol and burgers. The grassroots venue sector operates on a profit margin of 0.2% and the people who run the venues are already working at well below minimum wage. There’s no leeway in that part of the sector - they can’t sell any more beer. Because of the contents of the standard industry contract, increasing the ticket price won’t increase support act fees - headline artists take a guaranteed fee plus a percentage after costs, typically in the range of 70-85%. An artist and their agency could agree to increase the amount being paid to support acts, some have actually done this, but that lowers the amount they can receive, and headline acts are also struggling to make touring work. The number of tours, and the length of tours, is collapsing for this reason - down 17% in 2022 and predicted to further decline significantly in 2023.

Support acts fees have to be increased. There isn’t any way to increase them within the current model. That might seem to be an unsolvable problem. It really isn’t.

Live music has an assessable short term, direct economic impact. That impact can be measured by fees paid, people employed, tickets sold, bar income. Music Venue Trust’s Annual Report 2022 can tell you the facts and figures on that direct economic impact, but the headline is that it’s £500 million of economic activity, generating £229 million of spend on live music. In recent years, the debate on impact has expanded to start to consider indirect impact - how do people get to the gig, what do they do on the way there, what do they do on the way back. Once the gig gets them off their sofa, instigates an economic activity, this new analysis is starting to consider the full impact of that individual decision. Broadly, this equates to another £850 million in consumer activity, based on evidence that for every £10 spent at a grassroots music venue £17 is spent elsewhere in the night time economy.

In the short term, therefore, we can justifiably describe a sector that is creating £1.35 billion in economic activity. Which might appear to make a £50 support act fee even more difficult to justify, but almost all of this activity is already struggling to show any profit at all. So we need to look elsewhere, beyond the direct and indirect short term impact. We need to look at what happens in the long term as a result of the support act on the bill.

The Police reunion tour 2007/8 consisted of 143 shows, with an average gross income per event of $2.53 million. 3.3 million people attended the shows, spending an average of $109.67 per head. It was the 19th highest grossing tour of all time. generating a total income of $362 million.

Tonight, circa 480 shows will take place in the UK’s grassroots music venue. About 150 of them will feature a touring headline act and be paying the support act the industry standard £50. Increasing that fee to £160, the equivalent of the amount that The Police got paid in 1977, just for the support acts playing tonight, would cost £16,500. Per week it would cost £49,500. Per year it would cost £2.6 million. That’s every support act, every show, restoring the support act fee to its 1977 level, for a total cost of £2.6 million.

Now, I don’t know how important that show at The Marquee was for The Police on that Wednesday in 1977 at The Marquee. Maybe it was a terrible night, maybe it was the one that signed them to A&M. But I do know that on some night in some small venue somewhere, The Police went from being the support act to being the headline act. And we can easily track the long term financial impact that this moment had on our industry and on the economy, because that £20 support fee for that night

eventually turned into over £300 million. On just one tour.

What I do know is that we could be paying every single support act performing at every single show in the UK the fee that The Police got in 1977, £160, trebling the current fee we can afford to pay them, simply by asking that people who attended The Police tour in 2007 paid £0.78p extra. That’s asking that they pay $110.64 per ticket instead of $109.67 per ticket. Just one tour.

These numbers are so vastly out of step with each other that they can sometimes make you feel like you’re losing your grasp on reality, so let me throw another psychedelic morsel into your thinking and see if it causes the picture to swim into focus. The three major music companies, Universal, Sony and Warners, are now generating an estimated $2.9 million of income every hour. It would take 1 hour and 7 minutes of this income stream to generate all the money needed to pay every single support act in the UK £160 on every show taking place this year at every grassroots music venue. Assuming they were minded to do it for the US, Australia, Europe etc, it might take all of seven hours of income to make this happen everywhere in the world - 0.07% of the total annual income.

The long term impact and outcomes of every aspect of the work that grassroots music venues and artists deliver needs to be factored in to how we financially support these absolutely vital activities. If we don’t do that, we are throwing away the potential of the next act that just possibly might be The Police.

Heartily agree with this post! Here's my experience as a humble venue promoter..

50% of shows I have no say over the support & there is tour support in place

25% I’m asked for my suggestions (subject to mgmt approval) and the remainder I can control.

On my costings I set support fees at £100 as std.

And almost always the agent says that’s excessive and takes it down to £50.

That’s their decision and/or the mgmt of the headline act.

So when artists complain about support fees, and they are right to, it is (in the majority of cases) not something I have control over.

I’ve been thinking about this all weekend (and for years of course). Not least because this extends to the low fees that GMVs pay.

Is record label restoring your support the answer then? That’s what I take from your article, but any kind of pipeline investment fund would do?

My understanding was that £50 stuck around because if paying £0 was an option it would happen more. But there’s some ancient case law that set the contract standard at £50. Could be an old promoters’ wives’ tale. An old hand at Asgard could be worth asking, say Paul Charles?

Here’s who’s not been increasing the fee:

Headline artists and their agents. They need the dough themselves.

Promoters. Not getting the choice most of the time.

Arts Councils, other funding bodies. Though PRSF have certainly made contributions. Outwith them, the expectation is that the market sorts the rock n roll wheat from the chaff. Well it’s not doing it, it’s sorting the rich from the poor.

Export funds (lack thereof). Canada, Aus, Ireland, lots of other countries have incredible funding schemes for touring that should embarrass UK.

Audiences. Other than certain arena and stadium shows, the kind that court controversy over ticket pricing, the market is still price sensitive. Promoters could pay more if the ticket price was what it should be. I’d say ticket prices are up past CPI inflation this year. But venues’ costs are way up past that, as are touring act costs, so that’s your ticket price increase eaten (and then some).

Record labels (and let’s put publishers in here too). Lots reasons. There are so many more artists’ music released by all levels of labels now. How can they all get support? The long tail is extremely long and dragging.

But a record deal advance can still exist, for acts that can generate competition between labels. And publishers are increasingly where the up front dough is at. Regardless of whether some of it is hypothecated for touring, there’s sometimes a pot that could be used to make up the difference between rising artists’ costs and stagnant fees.

Here’s a sensible appeal to labels and publishers to get back into tour support:

If labels reinstated touring support for the acts they were most strongly picking as winners, I’d certainly want to know who was on that list. If nothing else, the signal to the rest of the industry that an new act had tour support could be worth much more than the actual cash spent. “Who are the buzz acts st Great Escape?”, “Well Columbia are giving your support to [XYZ bands], and UMG are are sorting out [*^¥ bands]”... “sound well then I know who to book”.

All well and good an agent tells me their act has 20m combined streams. Tell me they can afford to tour because the record label gave them dough, and I will book that show.