The Plug

What happens when you tug the wrong chain in the cultural canal

A man once hauled a wooden plug out of the bottom of a canal without realising what he’d done. That’s the whole story in one line, but it deserves a little more digging into, because it reads like something a bored Victorian novelist would have written after too much port. It is, however, true. It happened in 1978 on the Chesterfield Canal near Retford. Three workers were dredging the waterway, clearing out the usual collection of rusting bikes and prams and appliances that people hurl into canals when they’re drunk or newly single. They found an iron chain wedged deep in the mud. They tugged it. The chain refused to budge. They got the dredger. One good pull and up came the chain, with an old block of wood attached. While they went off for a nice cup of tea the canal quietly vanished.

A passing policeman spotted the whirlpool first. The water level was dropping so fast that boats were slumping sideways into the mud like dogs being told to play dead. By the time the workers returned a mile and a half of water had gone. The Danish holidaymakers who’d been cruising that morning now sat on the canal bed, stranded in a way they definitely hadn’t planned for. It took a little while for the truth to dawn. That innocent looking block of wood they had tugged out was a 200 year old engineering plug that James Brindley had installed when the canal was first built. Its entire job was to let someone drain the water safely into the nearby River Idle. The system worked perfectly; the problem was that nobody remembered it existed.

Generations of workers had come and gone and records of how the canal was constructed had been lost in the Blitz. The little scraps of localised knowledge that get passed down at the start of a shift or over a pint in the pub had vanished with the people who once knew them. A quiet bit of eighteenth century engineering just sat there beneath the silt, waiting for a modern machine to tug it free.

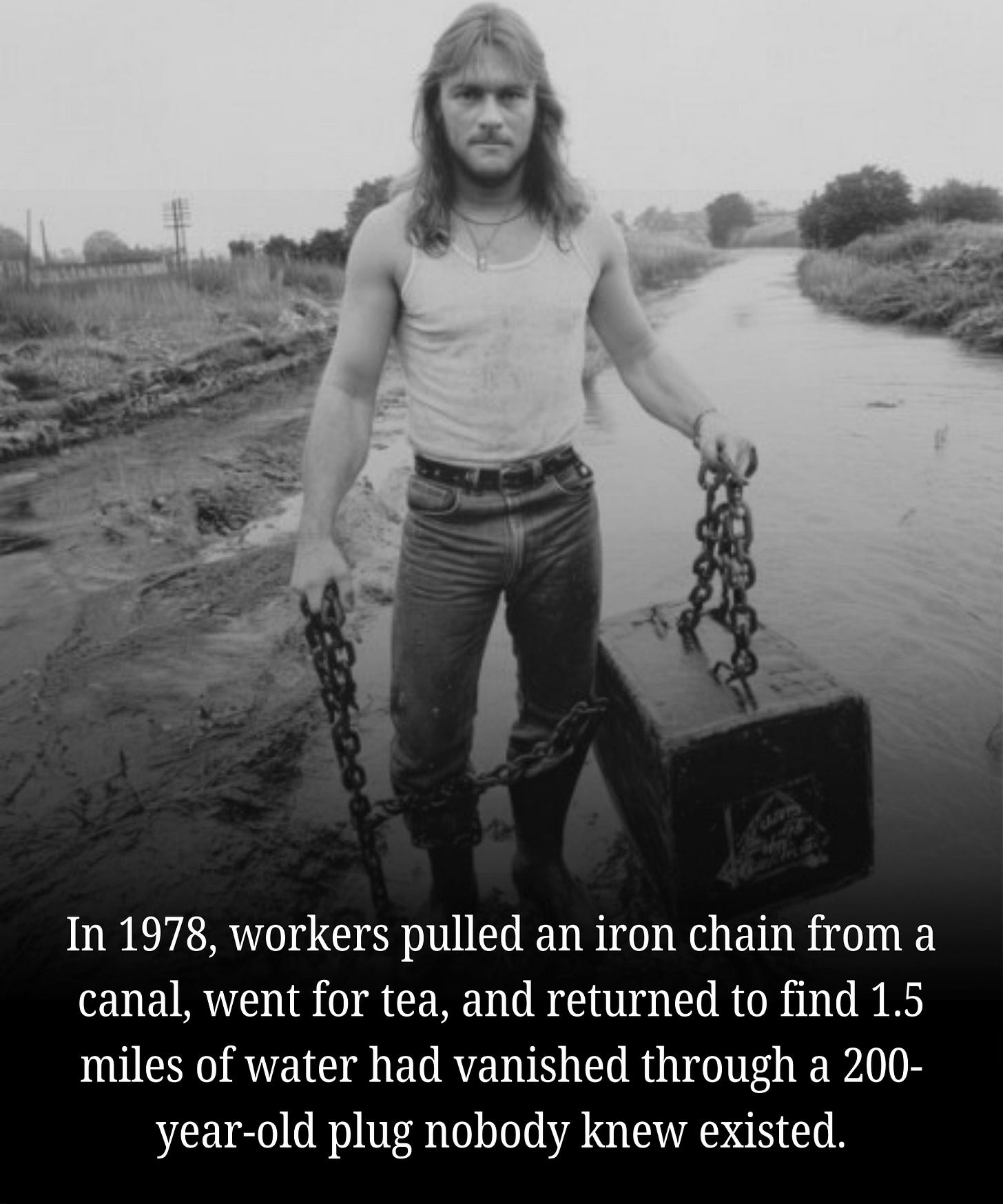

There’s a photo of a man holding the plug. He wasn’t actually the one who pulled it. He just worked nearby and got lumped with immortality because he had a decent mullet, looked bit like you imagine a water god might look, and turned up at the wrong moment. Television crews arrived to film the canal that went down the plughole. Boats high and dry, local workers blinking at the crater they’d made.

Of course, I’m telling you about this because there’s a rather obvious moral to the story. Before you pull a mysterious chain, make sure that it wasn’t put there, maybe centuries ago, for a rather good reason. And, perhaps more importantly, remember that the things you don’t know you’ve forgotten can cause serious problems.

Which brings me, inevitably, and you knew it would, to grassroots music venues.

The canal story has become a slightly absurd parable for what happens when you underestimate infrastructure. You think you’re shifting a bit of debris and so you think nothing will come of it. Then the whole system collapses while you’re on a tea break. And in our case, the system holding everything up is the fragile network of small venues scattered across the country.

These rooms are the plumbing of British culture. They sit quietly beneath the surface while the arenas and stadiums swell above them. The industry loves to talk about talent pipelines and economic impact, yet the place where the pipeline actually begins is a room with a stage that might not make it through the next electricity bill.

This year, more than 200 venues needed emergency help to avoid closure. That is one in four. The average venue made £3114 in profit across the whole of 2024. Not per gig, per year. In that same year, more than 25 million arena and stadium tickets went on sale, pumping record sums through the top of the industry while the bottom tried to cover its energy bill by selling nachos.

And while all this is happening, the touring map is evaporating. In 1994, an average tour covered nearly thirty towns and cities. In 2024, it barely reaches twelve. Leicester, Hull, Portsmouth, Stoke, Dundee. Towns that once saw national tours every week now sit on the dry bed of the old cultural canal, looking at the empty space where music used to run through their communities.

This is the part too often missed. When a venue closes, the loss isn’t neat. It spreads. Promoters lose work, local supply chains lose work, artists lose stepping stones, regional touring routes collapse, entire audiences lose access to culture. A venue never leaves a neat and clean outline so you can admire the shadow where it once stood and carry on as normal. It leaves a great big hollow that everything around it falls into.

And once the water drains in this canal, you can’t refill it by announcing you are aware of the problem. You refill it by recognising that an ecosystem only survives if the smallest parts of it are looked after. The £1 grassroots levy is the simplest expression of that. A pound from the most successful end of the industry to sustain the most vulnerable. It is not radical, it is the cultural equivalent of noticing that someone has pulled the plug and deciding not to stand there while the water drains away for the thrill of seeing if you can spot that bicycle your mate threw in the canal twenty years ago.

Rising energy bills, falling ticket income, transport systems that stop before the encore, noise complaints from buildings that should never have been approved. One by one, these are the chains that people are tugging on without thinking about it, and very often without even knowing they are doing it. Each looks small. Each looks manageable. Then you turn round and discover a town that no longer has a way for its young artists to start, a region that no longer sees touring acts. And you end up with a whole sector that relies on crowdfunders and emergency grants just to make it through January.

This is the quiet truth that sits beneath everything Music Venue Trust has spent ten years saying. A grassroots venue is not important because it might one day produce the next big act. It is important because it is an access route to culture in its own right. It is a public good. It is a local asset. It is one of the very few places in a town where people still gather to experience something live, something unfiltered, something shared.

Strip those places away and the consequences aren’t immediate. They are slow at first. You barely notice the waterline dropping. Then trains stop running late enough for people to attend gigs. Then mid level touring shrinks, a whole generation of artists can only play in six or seven major cities, and parents in smaller towns tell their kids that music is a thing that happens elsewhere. The entire pipeline silts up until, decades later, someone looks back and wonders how the UK, once one of the most fertile ecosystems for new music on earth, quietly drained itself.

The Chesterfield Canal Trust is still restoring parts of that waterway, half a century after the afternoon a little bit of it vanished. Grassroots culture is no quicker to repair, and very importantly, once it is lost it rarely reappears in the same place. Because when venues close down communities lose confidence. Buildings get repurposed, skills disperse, local promoters retrain or move on. The cost of revival is much, much higher than the cost of protection ever was.

This is why every venue matters. All of them, not just the famous ones, and not just the ones that produce artists who later headline stadiums. Every single room is a lock in the cultural canal. Remove one and the pressure shifts across the whole system. Remove ten and whole regions are left dry. Ignore all of them and, before long, the only places left with access to live music are the ones hooked up to the mains water supply - and I could write a whole other metaphorical Substack about letting companies like South East Water have the unique decision-making control over who does and does not get water and what the quality of it will be. In brief, based on the current fiasco in Tunbridge Wells; I would not recommend it.

The workers who pulled that plug in 1978 didn’t mean to drain anything, they thought they were hauling out rubbish. They didn’t know the chain was connected to two centuries of hidden engineering. Their mistake made international news because the consequences were so sudden and so bizarre. Our version is slower and quieter, but the principle is the same. Pull the wrong thing, ignore the warning signs, forget the history, and you discover too late that the structure beneath you is empty.

And in the last ten days we have had the perfect example of tugging at something without thinking about what it does and why it is there. The Government has been busy cleaning the water in our canal, bringing forward new multiplier calculators and a carefully designed Transitional Relief scheme to manage the future of Business Rates and keep culture on our High Streets. Unfortunately for them while they popped off for lunch the Valuation Office Agency had a quick go at Rateable Values and pulled the plug on the whole scheme, raising the rate for over 100 venues by more then 50%, many by more than 100% and a few by remarkable figures so bizarre they initially sound like a joke. The Government has planned for a nice full canal with lots of lovely clean water in it, but if they hang around for a cheesecake and an espresso, by the time they get back from lunch the canal will already be dry.

It’s better to do the work to keep the water where it belongs. Better to stop tugging on things that sometimes the people doing the pulling don’t really understand. In the case of the grassroots, it’s better to bring forward policies, legislation, and investment in the small rooms we have now rather than try to rebuild the whole canal years later with volunteers and hope.

The Chesterfield Canal emptying is a weird little story from fifty odd years ago which feels like it should be apocryphal but actually happened. The difference between that story and the story of the draining of our grassroots sector is that, this time, we know exactly what the plug is, what it looks like, and how important it is.

Don’t pull the plug. What we have is amazing.

You have chosen a great metaphor to explain this Mark. I love these updates and analogies but pray for the day when these posts are an archive to go back to, to see just how close we were to the collapse of GMV’s before something was finally done to turn this all around.

Great analogy Mark and all so true, the £1 levy is great and MVP is doing a great job, a venue at a time, so much more can and will be done quickly before the canal empties. 🙏🏾